Bed Bugs, Cimex lectularius, Cimex hemipterus and Leptocimex boueti (Heteroptera: Cimicidae)

Overview. Human bed bugs were virtually eradicated from the developed world in the middle of the 20th century. However, as of the first decade of the 21st century, bed bugs are back and winning. Bed bug infestations have been reported from all over the US and Europe, and California is no exception. Together with bat bugs, swallow bugs, and poultry bugs, they belong to the family Cimicidae in the suborder Heteroptera or true bugs (order Hemiptera). Cimicidae comprise less than 100 described species worldwide, but their notorious habits as temporary ectoparasites of birds and mammals, including humans, and the unusual mode of reproduction known as traumatic insemination, have made this small group of true bugs infamous. Recent interest in biology and ecology of bed bugs is now being reinforced by increasing numbers of household infestations on a global scale.

Morphology and Relationships to other Bugs. Bed bugs are small to medium-sized (4-12 mm), ovate, dorsoventrally flattened (i.e., squashed-looking from top to bottom) and of brownish coloration. Their wings are represented by short, non-functional wing pads and they cannot fly. Like other Heteroptera, Cimicidae have sucking mouth parts, and metathoracic and abdominal scent glands that produce a characteristic smell. The mouthparts comprise the labium (externally visible part of the “beak”) and pairs of maxillary and mandibular stylets that form the salivary and food canals. Bed bugs have several specialized features in common with some closely related groups, such as loss of simple eyes known as ocelli.

Bed bugs are closely related to the blood-feeding, bat bugs and predatory minute pirate bugs (family Anthocoridae) that are used as natural enemies in integrated pest management. The Cimicidae are divided into 22 genera, with 12 being exclusively associated with bats, 9 with birds, and only the genus Cimex containing a mixture of bird and mammal ectoparasites. Only three species may be associated with humans, Leptocimex boueti in certain areas of West Africa, Cimex hemipterus in the tropics of the Old and New Worlds, and, most importantly, Cimex lectularius in temperate and subtropical regions worldwide.

Natural History. Bed bugs belong to one of only three lineages within Heteroptera that are obligate blood feeders or hematophages. Similar to other obligate blood-feeding insects, cimicids have microbial symbionts in specialized organs that are presumably important for supplementing the blood diet. Most cimicids exhibit relatively narrow host preferences with either birds or bats as the dominant hosts. The host range extension from bat to humans in Cimex lectularius is likely to have taken place in Europe, the Middle East, or India, as humans moved from a cave-dwelling existence to living in villages and cities. The human bed bug subsequently spread with its new host around the world as people migrated with their belongings.

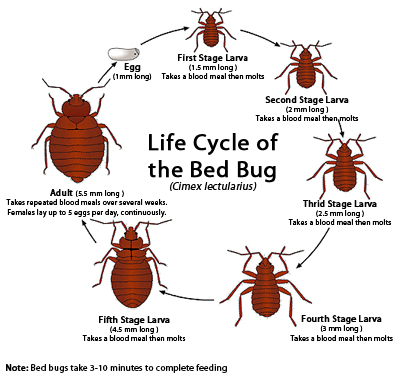

Because no life stages can fly, bed bugs rely on passive transportation by their host to spread. Consequently, they may hitchhike in suitcases, used furniture, and clothing. Moreover, an adult bed bug can survive for more than a year without a blood meal. Upon arriving at a new location, the prodigious fecundity of an undetected bug, 200-500 eggs per adult female, ensures a rapid increase in their numbers.Bed bugs are nocturnally active with peak feeding activity occurring after midnight. Bed bugs feed on blood about once every 1-2 weeks, while the host is inactive or sleeping. Feeding requires about 5-10 minutes to complete and generally occurs on areas of the body that are exposed while sleeping, such as the face, neck, arms, and hands. Bites may itch and a rash may develop around the bite. Bed bugs locate a host by orienting toward cues including heat, CO2,and host odors. When not feeding, bed bugs are generally concealed in cracks and crevices in their environment, including bed frames, head boards and mattresses. Their negative phototaxis (i.e. move away from light) and positive thigmotaxis (i.e. respond positively to tight spaces) makes them very difficult to locate during daytime hours when they are hiding.

In their resting places, bed bugs usually form aggregations of adults and immature stages that are maintained by aggregation pheromones and mechanical cues. When bugs are disturbed, substances emitted from scent glands function as alarm pheromones that drive dispersal and aggregations break up as bed bugs flee danger.

Apart from obligate blood feeding and host interactions, their unusual reproductive behavior has stimulated considerable research on bed bugs. Reproductive biology of Cimicidae is characterized by traumatic insemination, where sperm is not injected into the genital tract, but rather introduced into the female bed bug after the male pierces the female’s body wall with his reproductive organ. Traumatic insemination systems show tremendous species specific differences ranging from absent or simple to very complex and the study of reproductive structures used in this type of mating may provide insights into the evolution of this unusual mating strategy in the Cimicidae. Immature bed bugs (nymphs) release a chemical signal or pheromone to communicate their non-reproductive status to males, thereby protecting them from male mating attempts which might otherwise be very damaging.

While some viruses have been shown to persist within bed bugs for several weeks, their role in the transmission of human pathogens appears to be negligible. Nevertheless, bed bugs are serious nuisance pests. Infestation rates of human dwellings with bed bugs may reach 100% in some temperate regions and as many a 5,000 bugs may infest a single bed!

Bed Bugs, Humans and Infestation Management. The long and disturbing shared history of humans and bed bugs is reflected in language and legend. All Indo-European, African, and Oriental languages have names for bed bugs and these unpopular companions are mentioned in ancient Greek literature as well as the Talmud and the New Testament. Human sensitivity to the bite of a bed bug ranges from insensitive to severe immune reactions, and depends in part on the level of past exposure. Many people will develop hypersensitivity to bed bug bites following repeated feeding by bed bugs.

After a distinct decrease in infestation rates starting during the 1930s, bed bugs started to spread again in the 1990s. This spread is global, of dramatic proportion, and aided by increasing mobility of humans together with a decreased awareness of bed bugs due to their near absence within modern societies prior to their recent expansion. In North America, the resurgence in bed bug infestations has been aided by widespread resistance of these bugs to pyrethroid insecticides.

An infestation of bed bugs is usually identified by finding the bugs or their dark colored fecal stains in the seams of mattresses and box springs, behind headboards and peeling wallpaper, or in other cracks and crevasses near a sleeping area. The use of a strong flashlight will help in their detection because their strong aversion to light results in considerable movement. Heavy infestations are sometimes associated with a “sweet” odor. Trained dogs provide a very efficient means to detect bed bug infestations, especially when abundance is low, because the dogs can quickly determine by smell whether bed bugs are present in a room. Bed bug traps using CO2 and heat to attract the bugs may also be useful to identify infestations when bed bug abundance is low.

To reduce the opportunity for acquiring a new bed bug infestation, travelers should take the following precautions: 1) assess the room for the presence of bed bugs by a quick examination of the bed and bed frame, 2) avoid placing suitcases and clothing on the ground or room furniture, and 3) upon return home, launder all clothing (even those not worn) using the hottest settings for each fabric type, and store travel luggage in the garage.

Management of bed bugs within an infested premise is typically achieved using insecticides, though methods such as targeted vacuuming and heat treatment may also be utilized. The recently discovered pheromone which protects immature bed bugs from mating attempts by males has generated some interest as a possible control mechanism. Application of this pheromone to bed bug aggregation sites within an infested home may reduce male mating even with mature females and this could cause populations to collapse.

More Media on Bed Bugs

BedBugs.org: What are Bed Bugs?

BadBedBugs.com: Photos of Bed Bug Bites, Infestations and Pest Control Tips

WebMD: Bed Bugs Directory

BedBugRegistry.com: A Bed Bug directory, iOS app

University of California News: A trap for bedbugs?

ForestryImages.org: Bed Bug Images

YouTube: Video on Bed Bugs from various lab settings

YouTube: National Geographic Bed Bugs

- Boase, C. J. 2004. Bed-bugs - reclaiming our cities. Biologist (London) 51: 9-12.

- Carayon, J. 1959. Insemination par "spermalege" et cordon conducteur de spermatozoides chez Stricticimex brevispinosus Usinger (Heteroptera, Cimicidae). Rev. Zool. Bot. afr., Brussels 60: 81-104.

- Harraca, V., C. Ryne, and R. Ignell. 2010. Nymphs of the common bed bug (Cimex lectularius) produce anti-aphrodisiac defence against conspecific males. BMC Biology. 8:121.

- Pfiester, M., P. G. Koehler, and R. M. Pereira. 2009. Sexual conflict to the extreme: traumatic insemination in bed bugs. American Entomologist 55: 244-249.

- Pinto, L. J., R. Cooper, and S. K. Kraft. 2007. Bed bug handbook: The complete guide to bed bugs and their control. Pinto & Associates, Mechanicsville, MD.

- Reinhardt, K. and M. T. Siva-Jothy. 2007. Biology of the bed bugs (Cimicidae). Annual Review of Entomology 52: 351-374.

- Schuh, R. T. and J. A. Slater. 1995. True bugs of the world (Hemiptera: Heteroptera): classification and natural history, pp. i-xii, 1-336.

- Schuh, R. T., C. Weirauch, and W. C. Wheeler. 2008. Cimicomorphan relationships (Insecta: Heteroptera): combining morphological and DNA sequence data (Insecta: Heteroptera). Systematic Entomology, in press.

- Usinger, R. L. 1966. Monograph of Cimicidae. The Thomas Say Foundation, Vol. 7. College Park, MD.

- Zhu, F., J. Wigginton, A. Romero, A. Moore, K. Feruson, R. Palli, M. F. Potter, K. F. Haynes, and S. R. Palli. 2010. Widespread distribution of knockdown resistance mutations in the bed bug, Cimex lectularius (Hemiptera: Cimicidae), populations in the United States. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 73: 245-257.

Center for Invasive Species Research, University of California, Riverside

Text provided by Christiane Weirauch and Alec Gerry, photos by Christiane Weirauch, Alec Gerry and D.H Choe

Christiane Weirauch, Associate Professor of Entomology

christiane.weirauch@ucr.edu

Personal Website

Alec C. Gerry, Associate Extension Specialist

alec.gerry@ucr.edu

Media within CISR is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Permissions beyond this scope may be available at www.cisr.ucr.edu/media-usage.